A paramedic pumps nasal spray into an unconscious person’s nose while placing a ventilation bag over their mouth to get them to breathe. In less than half a minute, they’re conscious and animated, with open eyes.

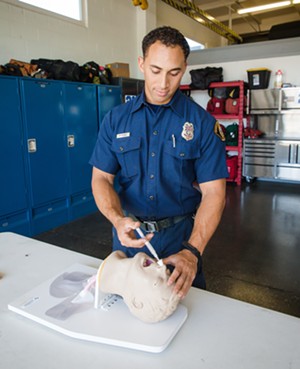

“There’s no question in my mind when this person is not breathing and I give them this—and 20 seconds later they’re now talking to me—that it was an opioid overdose,” Daniel Haynes described as he held up a naloxone container.

Commonly known as Narcan, the medication administered through the nose, as a shot, or as an IV reverses any opioid’s effects on the body. Haynes, an engineer paramedic for county Fire Station 21, said it’s an item every Santa Barbara County paramedic carries, and it’s life-saving when responding to overdose calls.

“It’s pretty cool because you’re dealing with somebody potentially who’s not breathing at all—they have minutes, potentially seconds to live, and you start and a minute later, they could be talking to you,” Haynes said.

When someone takes an opioid, the drug binds to opiate receptors in the brain, and too many opiates in the system—or an overdose—creates dangerous bodily effects, he explained.

“Decreased respiratory rate, or completely [lost] respiratory rate, is our main concern because that’s what’s going to kill you the quickest,” Haynes said.

Narcan binds itself to the brain’s receptors and kicks off any attached drugs. However, those drugs remain in the body, he said, so people need to go to the hospital to be monitored because the opioids can reattach themselves as Narcan’s effects wear off.

The tough part for Haynes and his team is knowing that Narcan only acts as a Band-Aid for people battling addiction—it simply extends a drug user’s life until the next overdose, he said.

“We’re not going to fix their addiction on-scene,” Haynes said. “I’ve been on calls where we’ve done this [administer Narcan] and woken the person up and took them to the hospital at 10 o’clock at night, and then we got called back to that house at six o’clock the next morning and they were dead.”

Santa Barbara County reported a record-breaking 133 opioid-related deaths in 2021. Fentanyl—a lethal opiate 50 times more potent than heroin—was cited as a leading cause of the increase. Since 2017, fatal overdoses in the county have nearly doubled. While working to plug holes in a porous system, county Sheriff Bill Brown and other local leaders believe that starting a dialogue is the first step to reducing overdose deaths.

“A lot of people have this, ‘Oh, well it’s not my problem. I don’t use drugs. My kids don’t use drugs.’ Well, guess what? Next week, your kids could be using drugs, and I guarantee there’s somebody in your neighborhood that’s using drugs,” Sheriff Bill Brown said. “This is all of our problem, and instead of people trying to hide it, [awareness encourages people] to come out and admit what’s happening and get some help.”

Poison, not overdose

While recovering from surgery in 2021, Brandon Claude couldn’t get his pain medication prescription refilled so he went to a neighbor for help. He unknowingly took a fentanyl-laced pill, Claude’s mother, Connie Branquinho, told the Sun.

“That day Brandon died, my life changed. There’s a life before May 30, and a life after May 30,” she said. “My son made a poor decision that day, but he didn’t deserve to die.”

Claude never used drugs because he’d witnessed his brother go in and out of treatment for addiction, Branquinho said, and she knew her other son didn’t want to be on the same track. After his death, Branquinho joined Let’s Make a Difference—a Santa Maria-based nonprofit that provides support for families and sponsors people through treatment—where she learned more about the fentanyl crisis and the drug’s severe effects.

“Fentanyl is so potent it takes one time to be hooked or kill you, like my son. It’s all mixed now; it’s in everything, and that’s the problem. The people doing drugs, like cocaine, have no clue they are getting fentanyl too, and that could kill them,” Branquinho said. “That’s why my son was pronounced dead of fentanyl poisoning, because he had no clue he was taking fentanyl.”

The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) seized 3.2 million counterfeit pills in 2021—a 2.2 million increase from 2020, said DEA Los Angeles Special Agent in Charge Bill Bodner. In the first quarter of 2022, the DEA seized more than a million.

“Projecting that, it would put us over 4 million, which is a 30 to 35 percent increase from last year,” Bodner said.

The majority of counterfeit pills containing fentanyl are produced by cartels in Mexico, Bodner said, signaling a shift from the drugs they’ve traditionally profited from, like marijuana and heroin. He attributes this to cartels wanting to cut costs.

“Just like a corporation, they wanted to see what they could do to increase their profits,” he said. “Heroin is labor-intensive; it’s grown with poppy plants, [and] a lot of the violence in Mexico is territory battles.”

Producing a synthetic drug like fentanyl requires less labor and no land, Bodner said, because cartels only need access to chemicals to create the drugs. Economically speaking, synthetic pills—which are designed to look like ordinary prescription pills—increase profits, Bodner said.

“The reality is there [are] no pharmaceutical ingredients in them,” he said. “They are the same shape, color, and stamping on them, but they are not the same.”

This deception is creating an “incremental” increase in overdoses and shifting first responders’ and law enforcement’s reality, he added, with recreational drug users playing a “very significant part.”

“There’s no long history of drug use; they are overdosing and dying,’” Bodner said. “A whole new group of people is susceptible to death.”

At the retail end of the supply chain, drug dealers are mixing the opiates with stimulants (like cocaine) to create a “perfect, euphoric high,” he added, but people taking the drugs are unaware of fentanyl’s presence.

“If you are expecting fentanyl and get coke, you will be pissed off. If you expect coke and get fentanyl, you will be dead,” Bodner said.

‘Dying at faster rates’

Even if fentanyl is a leading contributor to an overdose death, Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Lt. Robert Minter said it can be challenging to identify it as the cause of death.

“Usually with multiple illicit drugs in the system, it’s hard to say and pinpoint which drug caused the death,” Minter explained.

In order to see if fentanyl is in someone’s system, a coroner will draw bodily fluid (typically blood) for toxicology testing, he said. The doctor and detectives analyze the breakdown of substances in the body in order to pinpoint the cause of death.

The county Coroner’s Office has seen a “drastic increase” of overdoses where fentanyl was in the system, Minter said. In 2020, 36 of the 114 fatal overdoses contained fentanyl, and in 2021, 67 of the 133 had fentanyl.

“That’s not saying fentanyl was the leading cause of death, but it was in the toxicology report,” he said.

From January to July of 2022, there were 111 opioid-related overdoses reported in Santa Barbara County, with 50 involving fentanyl, Sheriff Brown said.

“When I started here, [overdose rates] were in the high 40s, 50s—50 people give or take—that would die, and then last year, we had 133,” Brown said. “It’s a crisis really; it’s something we have to do something about, and I wanted to sound the alarm and just get people aware that this [is] a very real problem that we’re experiencing in Santa Barbara County.”

To do this, Brown started Project Opioid, which follows a similar model to Florida’s Seminole County, where local leaders came together to compile overdose data, increase awareness of the issue, and provide better treatment-related services. Brown invited about 60 to 70 leaders from cities, county departments, nonprofits, school districts, and churches to join the first meeting in May 2022, which had about 34 individuals turn up. The following three meetings had similar attendance, Brown said in August.

“We’re now in the final stages of having put together an inventory of the services and everything that we already have,” he said. “The lowest hanging fruit of how we can save more lives is to make Narcan available in the community.”

Brown’s ultimate goal, he said, is to see a Narcan kit sitting beside a first aid kit and an automated external defibrillator in every public building.

However, as of Aug. 31 Project Opioid has no direct source of funding and no full-time staff dedicated to the project. The Sheriff’s Office was recently denied a federal grant to fund the program, and the project’s meetings are only three hours every month.

“We’re hoping to get funding for an executive director because we’re doing this all part time in addition to all the other things that we’re doing,” Brown said. “We really need a point person. All these other ones in Florida have somebody assigned to it full time.”

Project Opioid coalition member Pacific Pride Foundation—a nonprofit that serves the LGBTQ-plus community—has been running the county’s only syringe exchange program since 2002 where people can bring in old needles in exchange for new ones—and grab free Narcan.

“People often think syringe exchanges increase drug use, but that’s like saying a homeless shelter increases homelessness,” Pacific Pride Executive Director Kristin Flickinger said. “It’s incorrect; all it does is ensure people are not sharing needles and ensures that people have the tools they need to keep themselves alive.”

The program began in Isla Vista and now has in-person services in Santa Barbara and Santa Maria. Once a week, Pacific Pride volunteers and staff travel in a “health utility vehicle” to provide services that help reduce risk for blood-borne diseases like HIV and hepatitis C.

Now, the nonprofit’s noticing that once a week isn’t enough. The foundation wants to expand how often it hosts the syringe exchange and add a Lompoc location, Flickinger said.

“However you feel about drug use, I think [we] can agree we don’t want people to die, and people are dying at faster rates,” Flickinger said. “People who come to syringe exchanges and seek services are more likely to get help when they are ready for that than people who don’t.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), syringe exchange programs are safe, cost-effective, prevent disease, do not increase illegal drug use, and the provision of Narcan decreases opioid overdose deaths.

“Research shows that new users of [syringe exchange programs] are five times more likely to enter drug treatment and about three times more likely to stop using drugs than those who don’t use the programs,” according to the CDC.

Flickinger came to understand that her opinion on needle exchanges means “absolutely nothing”—the fact is they help save people’s lives, she said.

“What matters is whether or not they have the tools they need. It’s important to set aside the stigmas you have with drug use, LGBTQ-plus people, and help whatever way you can,” Flickinger said.

Death prevention

In 2021, Pacific Pride began distributing fentanyl strips—pieces of paper that change color if fentanyl is detected in a substance—and is the only organization allowed to do so through an exemption provided by the state and the Sheriff’s Office, Flickenger said.

“This is a key tool in the battle against opioid overdose for what we are starting to talk about as opioid poisoning,” she said.

State and federal laws classify testing strips as drug paraphernalia and prohibits possessing them. In response, Pacific Pride and other community organizations advocated for AB 1598: a 2022 state bill that legalizes testing equipment.

California Assemblymember Laurie Davies (R-Mission Viejo) proposed the bill in order to prevent fentanyl poisoning among young people in her community.

“Before I came up to Sacramento for Assembly, I was serving on the Laguna Niguel City Council and working with police services losing children to the opioid crisis,” Davies said. “We created programs and educational events for parents and teens. When I came up here [to Sacramento], fentanyl became much bigger.”

AB 1598 removes testing strips from the paraphernalia category, allowing for their distribution and use to test substances for fentanyl and ketamine, Davies explained. The bill passed through the Legislature and was signed into law on Aug. 29.

“I think you’re going to see lives saved,” Davies said. “It’s a really good precaution measure, interesting to see what the numbers are once they start coming in. It just gives us another tool to prevent someone from overdosing and dying.”

Medical-assisted treatment centers like methadone and buprenorphine clinics can also save lives through addiction treatment, said John Doyel, the county Behavioral Wellness Alcohol and Drug Programs Division chief.

“It doesn’t matter what the drug is, we have withdrawal management—formerly known as detox—residential treatment, outpatient treatment, intensive outpatient treatment, and after care,” Doyel said. “Some of our providers provide in-house medicated-assisted treatment, others link with providers.”

After an initial screening, the client receives methadone or buprenorphine—Food and Drug Administration-approved medications meant to treat addiction or pain—to assist with withdrawal symptoms and cravings all under a clinician’s watch, he explained.

However, county Behavioral Wellness and community organizations contracted with the county are having a hard time finding licensed clinicians, certified drug and alcohol counselors, and psychiatrists, Doyel said.

“We’ve got a real workforce problem; if we do have the money and positions, it’s difficult to find them,” he said. “We need more prevention, more public health models because treatment cannot keep up with the condition [of the] epidemic.”

Reducing stigma

Santa Maria resident Danielle Murillo called her experience with Behavioral Wellness a little frustrating after seeing her own son go through county treatment programs.

“If you are on MediCal, you have to call the hotline number and go through Behavioral Wellness and be assessed in order to get any programming they have,” Murillo said.

Self-paid, privately run programs often won’t accept MediCal and will direct people with state medical health coverage to a public program for assessment, plus those private programs often cost $600 to $700 a month, she said.

“We put him in and out of treatment for five years. [My ex-husband] put him in, and my son would leave,” Murillo said. “When your child is actively using, they are not themselves. You want your child back. You end up mourning a child that’s still living because they don’t have the personality of the child you had.”

There were periods when her son wouldn’t use for six months, but then he would relapse. One day in 2018, he overdosed on heroin while his girlfriend was in the shower and was rushed to the hospital, placed on life support, and passed away at 27, she said.

“I wanted to use his story to help save the lives of other people. I did not want his life as an addict to [have] a negative impact on people. I didn’t want his life to have a negative stigma, I didn’t want it to be considered dirty taboo, I didn’t want it to look like I was a horrible mom,” Murrillo said. “I needed something positive to come out of it. I am not ashamed of my son, and I’m not ashamed of being his mom, and I need people to know that.”

After speaking with close friends, Murillo said she started a community awareness and educational event about overdose and addiction in Santa Maria—which ended up raising money to sponsor someone going through treatment.

Now known as Let’s Make a Difference, the nonprofit has hosted three educational community events and provided eight, one-time sponsorships for addiction treatment. Most members are either recovering addicts themselves or have lost someone to addiction, she said.

“We all have something in common, and we are all there to support each other,” Murillo said. “We come together as a safe place to express our emotions and get out some of those feelings we need to get out, and we understand each other.”

This year, Let’s Make a Difference hosted its fourth annual event on Aug. 31—International Overdose Awareness Day—during which several organizations provided information about opioid addiction and distributed free Narcan, and members (including Murillo) shared their experiences of loss with the community.

“It’s helped me in that I know I’m helping others, and I’m not dwelling on the loss of him,” Murillo said. “If we close up and not talk about it, we aren’t going to help anyone. We have to talk about it and share our stories; if we keep covering it up, we are never going to help anyone.”

Taylor O’Connor can be reached at [email protected].